日本語

The Instagram Egg

Have you seen the news?

"An Egg, Just a Regular Egg, Is Instagram's Most-Liked Post Ever"

This was the headline in the Food section (?) of the New York Times about two months ago. The news was that a photo of an egg - the universal symbol of the mundane and the ordinary - inexplicably got more Instagram likes than Kylie Jenner's birth announcement.

|

| The Instagram Egg has 3 times more likes than Kylie Jenner' thumb and baby hand. |

The egg is now Instagram's most-liked post ever.

Kylie Jenner's baby post is second.

Headlines from other news outlets:

"An egg has overtaken Kylie Jenner as most-liked Instagram post ever" (CNBC)

"How an egg beat Kylie Jenner at her own Instagram game" (The Guardian)

(In the CNBC and The Guardian, the egg news was in the Technology section)

As of February 23, 2019, the Instagram egg had 53 million likes.

But WHY?

I can see your eyes rolling: "But why are you sharing this non-news here?"

Well, because I found this non-news mildly irritating. Not the news itself, but its tone.

The tone was: There is nothing special about the egg. It's the most banal object in the universe. How the hell could it get so many likes?

The New York Times article nailed it:

"Is the egg encrusted in diamonds? Does the egg have a popular YouTube channel you’ve never heard of? Is a sexy celebrity holding the egg?

Nope. None of the above. Just an egg."

Just an egg???

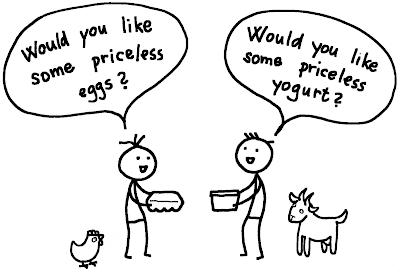

Our hens (and a rooster) would not agree.

If chickens could read a newspaper, the New York Times (and other papers) would be flooded with protest email messages.

But our chickens don't read newspapers and are busy enjoying their retirement, so they appointed me their spokesperson to write an angry response for them.

Now I have the grave responsibility of translating Chickenspeak to English and list some of the reasons why eggs deserve billions and trillions of likes.

The short answer is, because of the eggs' sheer number and importance in our lives.

LIST OF REASONS

Why an egg deserves 53 million likes

1. The world is flooded with eggs

This is more than 1,900 billion eggs. One thousand nine hundred billion eggs. In just one year.

This is in fact 1.9 trillion eggs.

In other words, we produce almost two trillion eggs every year to sustain the population of 7.8 billion humans.

Isn't that a mind-blowing number.

2. We eat eggs a lot

Eggs are not just sunny-side-ups and omelets. Eggs are used in a lot of foods: in many types of bread, pasta and nan; in baked foods, cakes, pies, cookies, puddings, pancakes, ice-cream, marshmallows, waffles, candy bars; in mayonnaise, salad dressings, tartar sauce and other sauces, soups, batter-fried foods, meatballs, meat loafs, tempura and okonomiyaki (the last two are mostly relevant in Japan)... and the list goes on.

In other words, we eat a lot of eggs. But we often don't know it. This of course doesn't change the fact that we eat them, and that there must be someone somewhere raising a lot of chickens that will lay those eggs for us - for that ice-cream or the pasta.

Some of us maybe thinking "I'm not a big egg eater anyway." Well, unless you're a vegan or egg-allergic, you're probably a bigger egg-eater than you think.

To sum it up, we use eggs in so many foods (and non-food products as well), that if eggs suddenly disappeared from the world, we would be in a lot of trouble.

We would certainly be in more trouble than if Kylie Jenner disappeared, from Instagram or from the world. (Of course I don't wish her that. I'm sure her family would miss her.)

Which, our hens (and a rooster) insist, is a good enough reason to agree that the Instagram Egg, as one of the 1.9 trillion eggs we use every year (laid by some 6.5 billion hens [Footnote2]), deserve a modest 53 million likes.

Sequel

The Instagram Egg story does not end here though. The sequel was published in The New York Times on February 3 (this time in Style section).

"Meet the Creator of the Egg That Broke Instagram"Spoiler 1: The egg's creator was finally revealed.

Spoiler 2: The egg has a name, Eugene (although it's supposed to be gender-free).

Long story cut short, the creator and his complices decided that they want to use Eugen the egg's newfound fame to do something good for the world. They have recently taken up a cause: mental health.

This is wonderful news!

Mental health is super important topic. Most people, including me, are probably not 100 % mentally healthy. Many of us have 1% or 5% or 83% mental issues. We struggle with stress and lack of sleep and lack of time to update blogs and to reply to friends and to travel and read books and climb mountains and study second partial derivatives.

I'm truly happy that Eugene the egg is now going to help us find help.

Now here's our chickens' proposal (translated for this article from Chickenspeak):

Eugene the egg should promote mental health of chickens too!

Most of the hens who lay those 1.9 trillion eggs in fact suffer from poor mental health. There is no direct statistics about this, but it's pretty clear the hens are mentally struggling. The ones that struggle are those who spend their lifetime in a tiny wire cage where they can't do anything but stand or sit, which is a majority of the world's 6.5 billion population of egg-laying hens. It's 24/7 of physical discomfort and utter boredom. There's no doubt their physical and mental health suffer.

To be clear, chickens surely like to stand or sit. Standing and sitting are wonderful activities. But chickens also like to walk, run, jump, fly, perch, peck and scratch the ground in hunt for anything edible, groom and dust bath (the last two are major social activities), and they like to lay eggs in the privacy of a nest. This is what being a chicken means. If they can't do any of these activities, they can't be a chicken, and that's stressful. Just imagine you were born a human but then couldn't do anything a human needs to do to feel like a human - sleep in comfort and safety, take a shower, go out for a walk, write a blog, reply to friends, travel and read books and climb mountains and study second partial derivatives....

If you couldn't do any of this, never, your mental health would suffer. Chickens are the same.

So, what if Eugen the egg also campaigned for the promotion of mental health of egg-laying hens?

The best start would be to let chickens do things they need to do to feel more chickeny.

That's the proposal of our chickens who, by the way, enjoy great mental health (as far as I can tell) and they wish the billions of their fellow chickens around the world could enjoy the same.

|

| Our chickens feeling chickeny. |

Footnotes

Footnote 1

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations gathers data on food production from all over the world. You can search their database, FAOSTAT, for virtually any agricultural item, including eggs.

So how do you arrive at the number quoted in this article: "1,953,493,339,000 eggs produced on planet Earth in 2017"?

1. Go to this FAOSTAT link (FAOSTAT Livestock Primary)

2. Choose the following in the four Select windows:

Click "Select All" in Countries

Select "Production Quantity" in Element

Select "Eggs, hen, in shell (number)" in Items

Select "2017" in Years

3. Click "Download Data"

4. Open the Excel file that you just downloaded.

5. Add up all numbers in Column L (Number of eggs produced in each country, from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe.) (Needless to say, use Excel SUM function for quick calculation.)

6. Multiply by thousand (because the unit of the column L is "1000" as specified in the column K.)

7. You should arrive at the number 1,953,493,339,000.

※The number 1.95 trillion includes only eggs laid by domestic chicken. Other birds - geese, duck, quail - are not included.

Footnote 2

The number of hens - 6.5 billion - is an estimate calculated by dividing the number of eggs (1,953,493,339,000) by 300, which is the average number of eggs that a normal hen of modern 'industrial' breed lays per year.

The actual number of hens on the world's egg farms is larger for several reasons, the biggest being the fact that the egg production cycle necessarily includes pullets - young hens before they start laying eggs. These are not included in the 6.5 billion estimate.

Also, the number 6.5 billion includes only domestic chicken (egg-laying hens), no other birds (no geese, ducks, quail).